By Dr Murthy Chavali Yadav

The author is Head of Department of Nanotechnology and Director of International Relations Office at

N I University, Kumaracoil, Tamilnadu.

Nanohybrids are composite materials comprising of two constituents at the nanometer or molecular level. In general one of these compounds is inorganic and the other one organic in nature. They differ from traditional macroscopic composites where the constituents are at the micrometer to millimeter level, mixing at this scale leads to a more homogeneous material that either to show characteristics in between the two original phases or even new properties. Organic/inorganic nanohybrids is a rapidly growing area of research because they offer opportunities to combine desirable properties of organic component (toughness, elasticity, formability) with those of inorganic solids (hardness, chemical resistance, strength). Owing to these, nanohybrid materials have been expansively studied for their superior properties over individual nanomaterials and molecules.

The term hybrid material is used for many different systems spanning a wide area of different materials, such as crystalline highly ordered coordination polymers, amorphous sol–gel compounds, materials with and without interactions between the inorganic and organic units. Before we expand on such materials let us try to delimit this broadly-used term by taking into account various concepts of composition and structure in table 1.

Categories

Hybrid organic–inorganic materials are not simply the physical mixtures of components, but can be broadly defined as molecular or nano-composites with organic and inorganic components, very well mixed where at least one of the component has a dimension ranging from a few Å to several nanometers. Subsequently the properties of hybrid materials are not only the sum of the individual contributions of both phases, but the role of their inner interfaces could be predominant. The nature of the interface has been used to segregate these materials into two distinct classes: (Sanchez et al (1994) New Journal of Chemistry, UK).

In Class I, organic and inorganic components are embedded and only hydrogen, van der Waals or ionic bonds give cohesion to the whole structure. These show weak interactions between the two phases, such as van der Waals, hydrogen bonding or weak electrostatic interactions.

In Class II materials, the two phases are partly linked together through strong chemical covalent or ion-covalent bonds. These show strong chemical interactions between the components. Because of the gradual change in the strength of chemical interactions it becomes clear that there is a steady transition between weak and strong interactions.

Typical interactions in hybrid materials and their relative strengths

Molecular approaches of molecular and solid state chemistry and nanochemistry have reached a very high level of sophistication. Chemists can custom make many molecular species and design new functional hybrid materials with enhanced and desired properties. Indeed, numerous hybrid materials are synthesized and processed by using soft chemistry routes based on:

- the organic functionalisation of nanofillers, nanoclays or other compounds with lamellar structures;

- the polymerisation of functional organo-silanes, macromonomers and metallic alkoxides;

- microporous metal organic frameworks,

- self-assembly or template growth,

- integrative synthesis or coupled processes, bio-inspired strategies, etc…

- nano-building block approaches, hydro thermally processed hybrid zeolites

- the encapsulation of organic components within sol–gel derived organo-silicas or

- hybrid metallic oxides;

Design strategies of Functional Hybrid Materials

Several technological breakthroughs gave way to the demand for novel materials for various new applications with desirable new functions. Scientists and engineers realized early mixtures of materials can have superior properties compared with their constituents. The combination of different analytical techniques gives rise to novel insights into hybrid materials and makes it clear that bottom-up strategies from the molecular level towards materials’ design that lead to novel properties in this class of materials.

Main chemical routes for all types of hybrid materials are schematically exemplified in figure 3. Though there were several of the chemical routes, in principle two different approaches exist in the formation of hybrid materials:

Either well defined building blocks are applied that react with each other to form the final hybrid material in which the precursors still, at least, partially keep their original integrity (or)

one or both structural units are formed from the precursors that are transformed into a novel (network) structure. Both methodologies have their advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of Combining Inorganic and Organic Species in One Material

Mixing two constituents offer opportunities to have desirable properties in combination of organic component (toughness, elasticity, formability) with those of inorganic solids (hardness, chemical resistance, strength).Certainly these nanohybrids are advantageous over other materials. The most obvious advantage of inorganic–organic hybrids is that they can favorably combine the often dissimilar properties of organic and inorganic components in one material (see table 2). Because of the many possible combinations of components this field is very creative, since it provides the opportunity to invent an almost unlimited set of new materials with a large spectrum of known and as yet unknown properties. Another driving force in the area of hybrid materials is the possibility to create multifunctional materials.

The advantage of hybrid materials is that functional organic molecules as well as bio-molecules often show better stability and performance if introduced in an inorganic matrix.

Improved properties – Enhanced heat distortion temperature and tear resistance without sacrificing elongation at break, special surface properties for functional materials, scratch-resistance, barrier resistance, halogen-free flame retardancy.

Cost effective and easy to process – Advantage of being melt process able.

Wide range of applications – Automotive, communication technology, MEMS, packaging, and textile.

Understanding fundamental characteristics of the organic-inorganic inter phase region by multi-scale analysis and its dependence on nano-element surface chemistry, that is the hybrid material behavior, can be considered a research frontier in this field.

This could lead to the formation of smart materials, such as materials that react to environmental changes or switchable systems, because they open routes to novel technologies, for example electro-active materials, electro-chromic materials, sensors and membranes, bio-hybrid materials, etc. The desired function can be delivered either from the organic or inorganic or even from both components.

Applications

Organic–inorganic nanohybrid materials do not only represent a creative alternative for the design of new materials and compounds for academic research, but their improved or unusual features open promising applications in voluminous areas: optics, electronics, ionics, mechanics, energy, environment, biology and medicine. Applications include smart membranes and separation devices, functional smart coatings, a new generation of photovoltaic and fuel cells, photocatalysts, new catalysts, sensors, smart microelectronics, micro-optical and photonic components and systems for nanophotonics, innovative cosmetics, intelligent therapeutic vectors that combine targeting, imaging, therapy and controlled release of active molecules, nanoceramic–polymer composites for the automobile or packaging industries, etc.

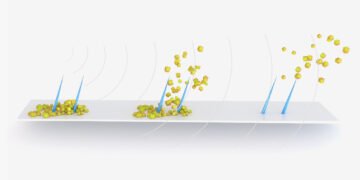

Simplest of all nanohybrids are nanoparticle/CNT nanohybrids, a brief summary of preparation and application of noble metal NPs/CNTs nanohybrids is shown in figure 4.So far, a variety of applications for nanohybrids has been investigated, of which a few were given under.

Sensors (Gas, Liquid, pH & Humidity) – Chemical sensor for the detection of aqueous ammonia has been fabricated using UV-curable polyurethane acrylate (PU) and 3 types of nanohybrids (NH-1, NH-3 and NH-5). PU has been prepared by reacting polycaprolactonetriol (PCLT) and isophoronediisocyanate (IPDI) while the nanohybrids, NH-1, NH-3, and NH-5 have been synthesized by solution blending method using PU with 1, 3, and 5 wt% loading levels of C-20B. PU and their nanohybrids showed higher sensitivity investigated by I-V technique using aqueous ammonia as a target chemical. The sensitivity increased with increase in clay content and the nanohybrid containing 5 wt% of clay showed the highest sensitivity (8.5254 μA cm(-2) mM(-1)) with the limit of detection (LOD) of 0.0175 ± 0.001 μM, being 7.8 times higher than pure PU. The calibration plot for all the sensors was linear over the large range of 0.05 μM to 0.05 M. The response time of the fabricated sensor was <10.0 s. Therefore, one can fabricate efficient aqueous ammonia sensor by utilization of nanohybrid as an efficient electron mediator.

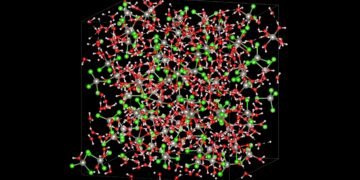

Nitrogen monoxide (NO) gas is highly reactive, participates in many chemical reactions, a vital messenger molecule has been the focus of study for several chemists during the past decades. Chavali et al (2012) have synthesized and characterized TWEEN-80/TEOS organic inorganic nanohybrids (see figure 5) via sol–gel route by microwave irradiation method to study the NO gas sensing at room temperature (300 K). The objective of this work is to overcome the limitations of existing sensors (like high temperature operation and low sensitivity).

Nanohybrid materials used over screen-printed carbon electrodes as electrochemical transducers for the construction of chemical sensors for mercury determination in water. The transducer with a nanohybrid surface of carbon nanotubes and gold nanoparticles was the best suited to solve the analytical problem. For this sensor, a calibration plot from 0.5 to 50 μg/L was obtained in acidic solutions of Hg(II) with an intraelectrodic reproducibility of 3%. The detection limit was 0.2 μg/L of mercury. The performance of the sensor was then evaluated using real samples of tap and river water with good accuracy.

Allyl-PEGcapped inorganic NPs, including magnetic iron oxide (IONPs), fluorescent CdSe/ZnS quantum dots (QDs), and metallic gold (AuNPs of 5 and 10 nm) both individually and in combination, were covalently attached to pH-responsive poly(2-vinylpyridine-co-divinylbenzene) nanogels via a facile and robust one-step surfactant-free emulsion polymerization procedure. VariedNPs injection is proportional to the swelling behavior. Furthermore, the magnetic response as well as the optical features of the nanogels containing either IONPs or QDs could be modified. In addition, a radical quenching in case of gold nanoparticles was also observed.

Environmental and Biomedical Applications – Nanostructured hybrids derived from clays are materials of increasing interest based on both structural characteristics and functional applications, including environmental and biomedical uses.Hybrid nanostructured clay derivatives (organoclays) are useful as adsorbents or photocatalysts for environmental applications such as removal of pollutants. A group of nanostructured materials considered related to bio-nanohybrids, formed by combination of an inorganic solid (clay mineral) with organic entities from biological origin at the nanometric scale.

Heterogeneous Catalysis – CNTs have received considerable attention as the supports of noble metal catalysts in heterogeneous catalysis due to their good mechanical strength, large surface area and good durability under harsh conditions. The interaction between noble metal NPs and CNTs in nanohybrids induces a peculiar microstructure or modification of the electron density of the noble metal clusters, and enhances the catalytic activity. The absorption of organic species is also favoured by van der Walls interactions between the CNTs andorganic molecules, leading to favorable reactant—product mass transportation.

CNT-supported noble metal catalysts (e.g., Pt, Pd, Au, Rh, Ru and Ag) exhibited good catalytic behaviour under various chemical reactions, involving Suzuki coupling, selective hydrogenation [102], CO oxidation and hydride halogenation.

Explosive detection – Amorphous silica nanoparticles are often employed as a matrix or carrier, along with a functional component, to form a silica-based nanohybrid. The functional component can be a molecule or another type of nanomaterial. These nanohybrids combine the advantages employing both silica and the functional component. The functional components include regular fluorophores, chemiluminescent molecules, drug molecules, quantum dots, gold nanomaterials, magnetic nanoparticles and nanocatalysts.

Antimicrobial – A facile and efficient aqueous phase-based strategy to synthesize silver nanocrystal/graphene nanosheet (GNS) nanohybrids at room temperature, via in situ poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) grafting followed by attachment of Ag nanocrystals, were made. In the presence of PAA-grafted GNSs, Ag nanoparticles were in situ generated from AgNO3 aqueous solution without any additional reducing agent or complicated treatment. They readily attached to the GNS surfaces, leading to Ag/GNS-g-PAA nanohybrids. The Ag nanoparticles can be uniformly deposited on the surfaces of functionalized GNSs with a controlled size distribution of 4-8 nm. Furthermore, the Ag/GNS-g-PAA nanohybrids exhibit good antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Escherichia coli. The mean diameters of the zones of inhibition are 11.4 mm and 9.9 mm, respectively, for S. aureus and E. coli. The simplicity, efficiency and large-scale availability of nanohybrids combined with good antimicrobial activity make them attractive for graphene-based biomaterials.

Dental applications – Modern nanohybrid composites enable the dentist to carry out restorations which are both minimally invasive and durable, and which combine the necessary stability with the optimum aesthetic effect required by the patient, especially for the posterior tooth.

Others -Nanohybrids as molecularly sensitive contrast agents. Specifically, agents produced by the company enable a new imaging tool, photo acoustic imaging, to non-invasively detect cancer, leading to highly advanced and personalized treatment strategies.

Organic-inorganic hybrids and coatings has been extended to incorporate functional organic molecules through either co-polymerization or self-assembly for applications including sensor, sorbent, and membranes. Optically transparent and anti-reflection super hydrophobic coatings have also been developed.

Bionano composites are an emerging group of nanomaterials resulting from the assembly of different clay minerals and biopolymers. Among the applications, the development of novel hybrid materials for scaffolds and regenerative medicine, as well as new substrates to immobilize biological species from enzymes to viruses, is notable.

Nanohybrid materials based on layered double hydroxides are receiving special attention in view of the possible applications as drug delivery systems. Hybrid materials have currently a great impact on numerous future developments including nanotechnology.

Further Reading

- Guido Kickelbick (Editor), Hybrid Materials: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA (2007), ISBN 978-3-527-31299-3, doi:10.1002/9783527610495.

- Ajayan P M , Schadler L S, Braun P V, Nanocomposite Science and Technology, WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA, Weinheim (2003).

- Sanchez, C and Ribot, F New Journal of Chemistry (1994) 18 (10), 1007.

- Sanchez, C, Julian, B, Belleville, P, and Popall, M Journal of Materials Chemistry, (2005) 15 (35-36), 3559.

- Kickelbick G (Edit), Hybrid Materials Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications, WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA, Weinheim (2007).

- Khan SB, Rahman MM, Jang ES, Akhtar K, Han H Special susceptive aqueous ammonia chemi-sensor: extended applications of novel UV-curable polyurethane-clay nanohybrid, Talanta. (2011) 84 (4) 1005-10.

- Ming-Ru Yu, Gobalakrishnan Suyambrakasam, Ren-Jang Wu, Murthy Chavali, Preparation of organic–inorganic (SWCNT/TWEEN–TEOS) nano hybrids and their NO gas sensing properties, Sens Actuators B 161 (2012) 938– 947.

- Daniel Martín-Yerga, MaríaBegoña González-García, Agustín Costa-García, Use of nanohybrid materials as electrochemical transducers for mercury sensors, Sens Actuators B: Chemical (2012) 165 (1), 143–150; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2012.02.031.

- Riedinger A, Pernia Leal M, Deka SR, George C, Franchini IR, Falqui A, Cingolani R, Pellegrino T, “Nanohybrids” based on pH-responsive hydrogels and inorganic nanoparticles for drug delivery and sensor applications, Nano Lett (2011) 11 (8) 3136-41.

- A Corma, H Garcia, A Leyva, Carbon Nanotubes as Supports for Palladium and Bimetallic Catalysts for Use in Hydrogenation Reactions, J Mol Catal A 230 (2005) 97.

- CY Lu, MY Wey, The performance of CNT as catalyst support on CO oxidation at low temperature, Fuel, 86 (2007) 1153-1161.

- JY Kim, Y Jo, S Lee, HC Choi, Synthesis of Pd–CNT nanocomposites and investigation of their catalytic behavior in the hydrodehalogenation of aryl halides, Tetrahedron Lett (2009)50, 6290.

- Tai Z, Ma H, Liu B, Yan X, Xue Q, Facile synthesis of Ag/GNS-g-PAA nanohybrids for antimicrobial applications, Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces (2012)1; 89, 147-51.

- Walter Denner, High quality restorations – Modern nanohybrid composites, an alternative for all cavity classes, Australian Dentist (Clinical), (2008) 58-59; Hugo, Burkard, ÄsthetikmitKomposit – Grundlagen und Techniken (mit DVD), QuintessenzVerlags-GmbH (2008), ISBN 978-3-938947-55-5.