It can be a significant challenge to cool the powerful electronics packed inside the latest smartphones. KAUST researchers have developed a fast and efficient way to make a carbon material that could be ideally suited to dissipating heat in electronic devices. This versatile material could also have additional uses ranging from gas sensors to solar cells.

Many electronic devices use graphite films to draw away and dissipate the heat generated by their electronic components. Although graphite is a naturally occurring form of carbon, heat management of electronics is a demanding application and usually relies on use of high-quality micrometer-thick manufactured graphite films. “However, the method used to make these graphite films, using polymer as a source material, is complex and very energy intensive,” says Geetanjali Deokar, a postdoc in Pedro Costa’s lab, who led the work. The films are made in a multistep process that requires temperatures of up to 3200 degrees Celsius and which cannot produce films any thinner than a few micrometers.

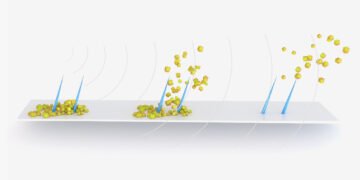

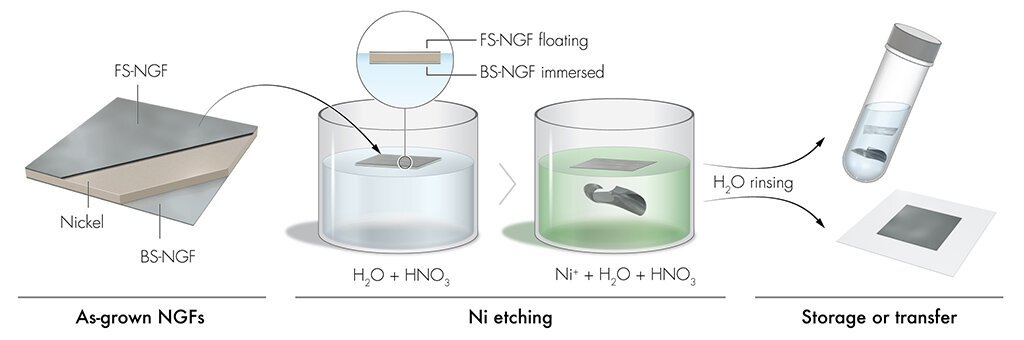

Deokar, Costa and their colleagues have developed a quick, energy-efficient way to make graphite sheets that are approximately 100 nanometers thick. The team grew nanometer-thick graphite films (NGF) on nickel foils using a technique called chemical vapor deposition (CVD) in which the nickel catalytically converts hot methane gas into graphite on its surface. “We achieved NGFs with a CVD growth step of just five minutes at a reaction temperature of 900 degrees Celsius,” Deokar says.

The NGFs, which could be grown in sheets of up to 55 square centimeters, grew on both sides of the foil. It could be extracted and transferred to other surfaces without the need of a polymer supporting layer, which is a common requirement when handling single-layer graphene films.

Working with electron microscopy specialist Alessandro Genovese, the team captured cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the NGF on nickel. “Observing the interface of the graphite films to the nickel foil was an unprecedented achievement that will shed additional light on the growth mechanisms of these films,” Costa says.

In terms of thickness, NGF sits between commercially available micrometer-thick graphite films and single-layer graphene. “NGFs complement graphene and industrial graphite sheets, adding to the toolbox of layered carbon films,” Costa says. Due to its flexibility, for example, NGF could lend itself to heat management in flexible phones now starting to appear on the market. “NGF integration would be cheaper and more robust than what could be obtained with a graphene film,” he adds.

However, NGFs could find many applications in addition to heat dissipation. One intriguing feature, highlighted in the TEM images, was that some sections of the NGF were just a few carbon sheets thick. “Remarkably, the presence of the few-layer graphene domains resulted in a reasonable degree of visible light transparency of the overall film,” Deokar says. The team proposed that conducting, semitransparent NGFs could be used as a component of solar cells, or as a sensor material for detecting NO2 gas. “We plan to integrate NGFs in devices where they would act as a multifunctional active material,” Costa says.