If such a world exists, metallic elements are likely the sources of the dissolved materials and particles in these oceans. Everything would be made of metallic elements, even lifeforms.

It may sound like a concept pulled straight out of a science fiction movie, but some basic elements of this fantastical vision can still be easily realized on our planet.

We are all familiar with growing crystals in water. The most obvious example is the growth of sugar crystals that many of us have done during our time at school. Here, sugar solute in a water solvent can precipitate as crystals out of the solution.

Now, Australian researchers have shown the possibility of an analogous observation with liquid metals as a solvent and published an exciting report in the journal ACS Nano.

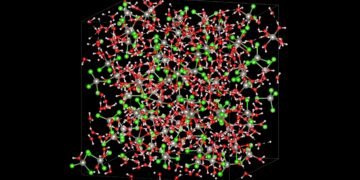

It is known that metallic elements can dissolve and form solutes in liquid metal solvents. It is also known that these secondary metals can form clusters of metallic crystals inside the metallic solvent. This is in fact the base of the well-established field of metallurgy. However, in metallurgy the primary interest is in solidifying solvents and solutes together to create solid alloys for a variety of applications.

The researchers at at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), School of Chemical Engineering looked at liquid metals from a different angle.

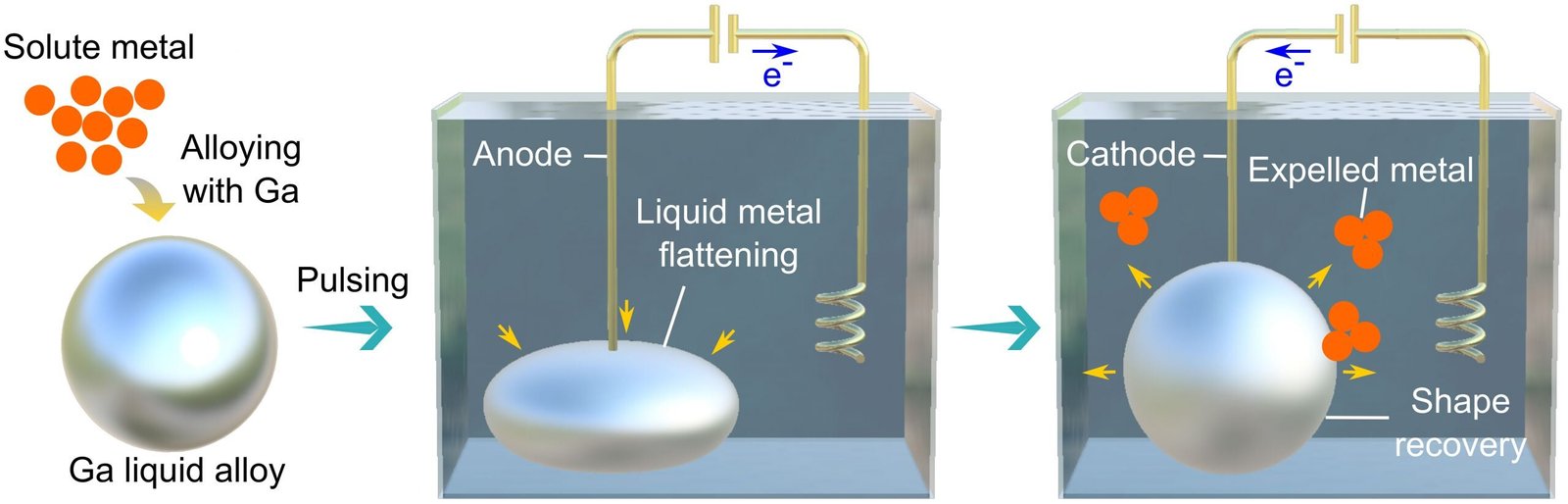

They used gallium, which is liquid at near room temperature, like mercury, and dissolved different metals into it.

Small crystals of these metallic elements formed inside the liquid metal.

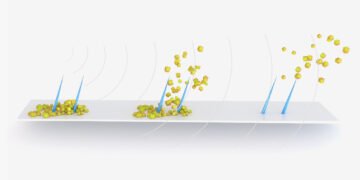

However, as the surface tension of liquid metal is quite high, these metallic crystals remained trapped inside the liquid metals.

High surface tension means that liquid metals are immiscible in other liquids and as such it is not possible for the metallic crystals to naturally free themselves into the surrounding.

The researchers discovered a new method to extract these metallic crystals out of the liquid alloy. By applying a voltage to the surface of a liquid metal droplet, they were able to reduce the surface tension sufficiently to allow the metallic crystals to be pulled out.

“We were able to make very small crystals that were of a metallic and metal oxide nature,” said Dr. Mohannad Mayyas, author of the paper. “We dissolved indium, tin, and zinc into gallium liquid and precipitated them out of the media by applying a voltage in a specific set-up. The method is really advantageous as making such crystals generally requires hazardous precursors and harsh synthesis conditions.”

“Other researchers can continue our work and explore the many possibilities that liquid metal solvents offer,” suggested Prof Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, the corresponding author of the paper. “For example, liquid metals are super catalytic. While the formation of crystals in aqueous solutions may take a long time, the creation of the metallic elements inside liquid metal can take place instantly. Additionally, liquid metals offer opportunities for intriguing interfacial chemistry that do not exist for any other systems.”