More efficient conversion of heat into electricity by tinkering with nanostructure

A graphical abstract of the research. Courtesy: Delft University of Technology.

Thermoelectric materials convert heat into electricity, which makes them extremely attractive for sustainable energy production, especially given that industry can waste more than two-thirds of its energy as heat. But mass production of thermoelectric energy is currently limited by low-energy conversion efficiency. Now, however, researchers Biswanath Dutta and Poulumi Dey of TU Delft’s department of Materials Science and Engineering, have not only been able to explain how nano-structures in thermoelectric materials can improve energy efficiency, but also propose a commercially attractive way to manufacture nano-structured thermoelectric materials, increasing the chances for mass production of thermoelectric energy. Their results were published in Nano Energy.

The starting point for Dutta and Dey’s work was the experimental results provided by their co-researchers in South Korea who were working with a well-known thermoelectric material, a so-called NbCoSn half-Heusler compound. “This is basically a specific type of crystal structure into which you put certain elements—in this case niobium, cobalt and tin,” explains Dutta. “And by playing around with both the amount and the position of each of the elements—for example putting more niobium in place of cobalt—you can see how that affects the overall efficiency of the material.”

What the results from their South Korean collaborators showed was that at a specific temperature, certain kinds of nano-structures were formed within this material. So Dutta and Dey ran theoretical simulations based on these observations: “Firstly we simulated the effect of adding either one or two extra cobalt atoms, and in various different positions, to find out whether that would increase the efficiency or not,” says Dey. “It turned out that the position of this extra cobalt really has an important role on the whole performance of this material, which was something that the team doing the experiments couldn’t really explain because it was beyond the resolution of their measurements.”

In addition, Dutta and Dey were also able to demonstrate an effect known as energy filtering: “You can think of it as a sort of barrier to electrons below a certain energy, which in turn improves overall electrical conductivity,” explains Dutta. “By filtering out the low-energy electrons and allowing the high-energy electrons to pass through, there is an increase in the overall efficiency.”

“This is a nanostructure effect,” says Dey. “It’s the formation of the nanostructures in the rest of the material, and the interface between them, that acts as the barrier so if you don’t have these nanostructures, you won’t have this effect because there’s no interface. But as soon as these nanostructures are formed, you get these interfaces which block the low energy electrons but allow the high energy ones to pass through with the result that the overall energy efficiency is increased.”

Ultimately, the TU Delft simulations suggested two reasons for increased energy efficiency in this tailored NbCoSn thermoelectric material: the presence of extra cobalt atoms in specific positions called interstitial sites within the lattice structure, and also the energy-filtering effect.

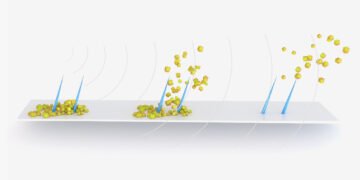

Moreover, the improved understanding of why this nano-structured thermoelectric material is more energy-efficient suggests a better, more applicable way to produce thermoelectric energy. “Currently, nano-structured thermoelectric materials are made through a long and rigorous process of crushing and heating pre-formed structures,” explains Dutta “which is both time and energy-consuming, so not ideal for mass production.” Rather than going down the conventional route, the teams suggested starting with an “unstructured” or amorphous material: “The advantage of starting with an amorphous material is that it doesn’t have an underlying structure and so you don’t need to go through this long process of grinding and heating for homogenisation. So it’s more energy efficient and therefore much more useful for mass production of thermoelectric energy.” Good news for engineers in those industries working on recovery of high temperature heat.