Human cells possess various proteins that act as channels for charged ions. In the skin, certain ion channels rely on heat to drive a flow of ions that generates electrical signals, which we use to sense the temperature of our surroundings.

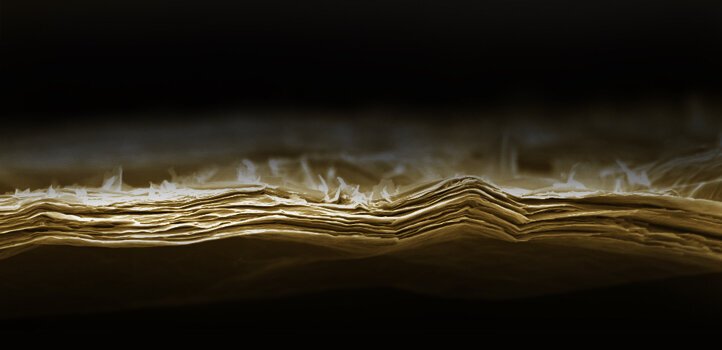

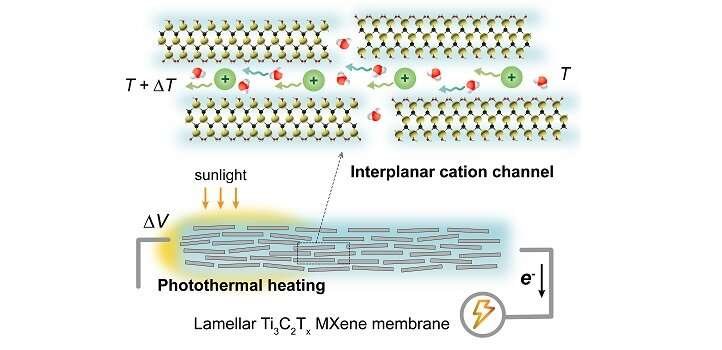

Inspired by these biological sensors, KAUST researchers prepared a titanium carbide compound (Ti3C2Tx) known as an MXene, which contains multiple layers just a few atoms thick. Each layer is covered with negatively charged atoms, such as oxygen or fluorine. “These groups act as spacers to keep neighboring nanosheets apart, allowing water molecules to enter the interplanar channels,” says KAUST postdoc Seunghyun Hong, part of the team behind the new temperature sensor. The channels between the MXene layers are narrower than a single nanometer.

The researchers used techniques, such as X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy, to investigate their MXene, and they found that adding water to the material slightly widened the channels between layers. When the material touched a solution of potassium chloride, these channels were large enough to allow positive potassium ions to move through the MXene, but blocked the passage of negative chloride ions.

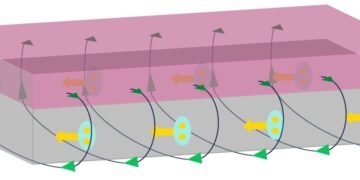

The team created a small device containing the MXene and exposed one end of it to sunlight. MXenes are particularly efficient at absorbing sunlight and converting that energy into heat. The resulting temperature rise prompted water molecules and potassium ions to flow through the nanochannels from the cooler end to the warmer part, an effect known as thermo-osmotic flow. This caused a voltage change comparable to that seen in biological temperature-sensing ion channels. As a result, the device could reliably sense temperature changes of less than one degree Celsius.

Decreasing the salinity of the potassium chloride solution improved the performance of the device, in part by further enhancing the channel’s selectivity for potassium ions.

As the researchers increased the intensity of light shining on the material, its temperature rose at the same rate, as did the ion-transporting response. This suggests that along with acting as a temperature sensor the material could also be used to measure light intensity.

The work was a result of collaboration between the groups of KAUST professors Husam Alshareef and Peng Wang. “We envision that the MXene cation channels have promise for many potential applications, including temperature sensing, photodetection or photothermoelectric energy harvesting,” says Alshareef, who co-led the team.