By Dr Yashwant R Mahajan

Introduction

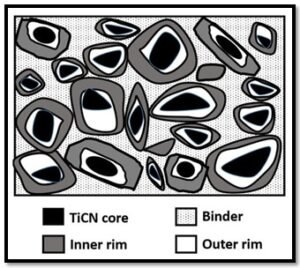

Cermets in general have been defined as “Composite materials comprising two constituents, one being either a ceramic (Cer) such as an oxide, carbide, boride, or similar inorganic compound, and the other one is a metallic (Met) binder”. The ceramic in general has high temperature resistance and hardness, and the metal has the ability to undergo plastic deformation.The metal improves the toughness and the thermal shock resistance of the ceramic. A cermet is preferably designed in such a way to endow the combined optimal properties of a ceramic and a metal. Metals such as cobalt and nickel and their alloys are usually used as a binder for an oxide, boride, nitride, or carbide. A typical schematic of a commercial cermet microstructure imaged using SEM is shown in Figure 1.

Figure-1: Schematic of a commercial TiCN-based cermets, the binder phase is mostly composed of

either Ni or CoJose, S.A.; John, M.; Menezes, P.L. Cermet Systems: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications.Ceramics 2022, 5, 210-236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics5020018.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The binder material itself can also contribute to the corrosion resistance because of its excellent intrinsic anti-corrosion attribute. Hardmetals (cemented carbide) comprise the most important class of the hard and wear-resistant materials industry. Unlike the main element of cemented carbide is WC, cermets use titanium carbide (TiC) as the main element. The binder metal used for cermets is mainly nickel (Ni). This is because Ni has higher adhesion strength to TiC than cobalt (Co). Though there are drawbacksassociated with this combination, one being that the bond strength between TiC and Ni is not as strong as it is between WC and Co. Thus, the toughness of cermets tends to be weaker and less ductile than that of cemented carbides. For example, the toughness of TiC-TiN-Ni isslightly higher than >10 MPa.m1/2 (Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiC–TiN based cermets for tools application).

To improve the toughness of cermets, the additions of materials such as molybdenum (Mo), titanium nitride (TiN) and other metal has been introduced. This led to development of TiC-TiN-Mo-Ni-based cermets that offer improved toughness and is today’s conventional cermet. The most widely used cemented carbide consists of tungsten carbide (WC) with about 6% cobalt. WC–Co cermets, also referred to as cemented carbides, have toughness of about 10–15 MPa.m1/2, which is due to the ductility of the cobalt. Pure polycrystalline WC has fracture toughness typically of about 3 MPa.m1/2.Hard metals or cemented carbides, especially WC–Co, WC-Ni and WC-TiC-Co are successfully produced commercially with a high degree of control and reliability in mechanical properties are used broadly in all sectors of industry to combat wear and corrosion. A few of the many applications include cutting tool inserts, valves, seals, saw teeth, liners of pharmaceutical (pill press) dies, and tooling for making cans. For further details the interested readers may please refer to an excellent review (Cermet Systems: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications).Cermets have been defined in different ways.

The present article uses the definition from (Comprehensive Hard Materials 1st Edition) :i.e.,cermets are ceramic–metal composites bonded with a metal matrix except for WC-based composites–hard metals (cemented carbides). Cermets consist primarily of ceramic particles, such as titanium carbonitride (Ti(C, N)) or titanium carbide (TiC), Ti(C,N)- and TiC-based cermets exhibit high hardness, exceeding that of WC-Co hard metals (at similar volume %of ceramic phase) and resistance to wear at high cutting rates as compared to hard metals. The most widely used metallic binders of cermets are Ni alloys(Comprehensive Hard Materials 1st Edition). However, during the last two decades, substantial research efforts have been directed towards employing Fe alloys as metallic components of cermets. Fe alloys have advantages over Co and Ni, such as high strength, potential to heat treatment and reasonable cost.

Despite their superior abrasion and wear resistance, cermets notoriously lack in their ductility and display inadequate toughness. In order to overcome this drawback significant efforts have been made by microstructural engineering and modifying the chemical composition to enhance their toughness and ductility

(Chemical Composition, Microstructure And Sintering Temperature Modifications On Mechanical Properties Of Tic-Based Cermet– A Review;A new family of cermets: Chemically complex but microstructurally simple, Micro-Nanostructured Cermet Coatings;Effect of Mo addition mode on the microstructure and mechanical propertiesofTiC–high Mn steel cermets ).

In spite of intensive efforts made by the researchers no ductility in cermets has been achieved as on date and this has been attributed to inherent brittleness of the ceramics (an important component of cermets).Interestingly, an important brittle ceramic component of cermet exhibits ductility, flexibility and toughness in its ultrathin form. For example, Corning developed ceramic sheets made with zirconia more than a decade ago for use in fuel cells, electronics, gas sensors, and other applications. These sheets show high flexibility without any evidence of breakage (Flexibility Matters: For both glass and ceramics, new innovations are bending the rules). Another example is Superlattice (SL) thin films composed of refractory ceramics (TiN/CrNsuperlattice structure) unite extremely high hardness and enhanced fracture toughness; a material combination which is often mutually exclusive. While the hardness enhancement is well described by existing models based on dislocation mobility, the underlying mechanisms behind the increase in fracture toughness are yet to be unravelled (Enhanced fracture toughness in ceramic superlattice thin films: On the role of coherency stresses and misfit dislocations).In cermets, ceramic being a major constituent there is every possibility that ultrathin cermet films could exhibit high hardness and enhanced toughness.

Experimental Work and Discussion

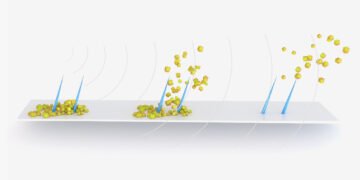

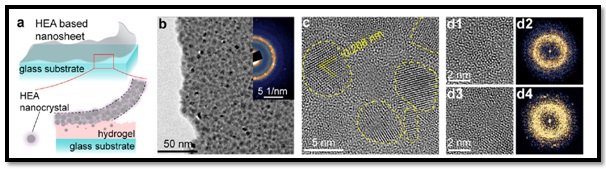

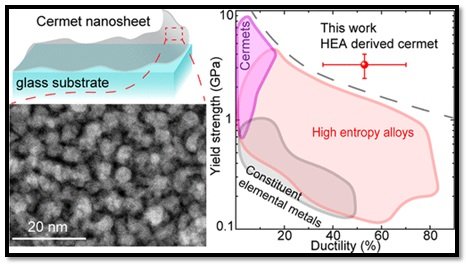

The researchers from a number of Chinese R&D institutions in their collaborative study (Strong yet Ductile High Entropy Alloy Derived Nanostructured Cermet),utilized a low-cost, high-yield scalable production method for 2D metals through polymer surface buckling enabled exfoliation (PSBEE), (Low-Cost Scalable Production of Freestanding Two-Dimensional Metallic Nanosheets by Polymer Surface Buckling Enabled Exfoliation) and synthesized ultrathin cermet nanosheets by depositing a high entropy alloy (HEA), FeCoNiCrCu had selected as a precursor via magnetron sputtering onto a PVA hydrogel thin film supported by substrates.The reason for making a choice of this specific HEA as a precursor because it is thermodynamically favourable (Controlled synthesis of nanostructured glassy and crystalline high entropy alloy films)for this alloy to be deposited in the form of nanocrystals as shown in Figure 2.

By manipulating the sputtering time, the FeCoNiCrCu alloy based freestanding nanosheets were prepared having different thicknesses (12 to 85 nm) were prepared. Figure 2 (b) shows a Low Mag. TEM image of the cermet nanosheet and the inset shown therein represents interrelated Selected Area Diffration Pattern (SADP). In this Figure, it clearly shows that the nanosheet comprises of individual nanocrystals surrounded by interphse having nanoscale thickness. Figure 2 (c) is an HRTEM image of cermet nanosheet and nanocrystals are represented by yellow dashed circles and Figures d1 to d4 (FFTimages) confirms that the interphase is amorphous in nature. The SADP shown in Figure 2 (b) substantiate that both crystalline and amorphous phases are present in the specimen.

Figure-2:Synthesis and structural characterization of the freestanding cermet nanosheet. (a) The schematic of the formation of the ultrathin nanosheet. (b) Low-magnification TEM image of the 20 nm-thick freestanding cermet nanosheet. The inset shows the corresponding SADP. (c) HRTEM image of the 20 nm-thick freestanding cermet nanosheet. Nanocrystals are highlighted by the yellow dash circles. (d1−d4) are the local HRTEM images and the corresponding FFT images of the amorphous regions that contain various degrees of ordering.

Figure 2-(e) HAADF-STEM image of the 20 nm-thick freestanding cermet nanosheet showing the nanocrystal phase (bright region) and amorphous phase (dark region).“Reprinted with permission from {Strong yet Ductile High Entropy Alloy Derived Nanostructured Cermet, Jingyang Zhang, Qing Yu, Qing Wang, et al, Nano Letters}. Copyright {Sep. 1 2022) American Chemical Society.”

The atomic force microscopy (AFM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were employed to characterize and measure the structural and chemical properties of the cermet nanosheets. The researchers scrutinized the nanoscale structure with the aid of high-angle annular dark-fieldscanning TEM (HAADFSTEM). As displayed in Figure 2 (e), the bright Z contrast of the nanocrystals (average size 5 ± 1.5 nm) denotes that they mainly consist of metallic elements (Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu) while the dark Z contrast of the amorphous interphase (average size 1-5 nm) can be attributed to the high concentration of light elements, mainly C, O etc. originating from the hydrogels or native oxides.

Based on the studies conducted with the aid of energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) equipped with STEM it can be concluded that the nanocrystals in the nanosheet are made up of metallic elements with a composition of near-equimolarFeCoNiCrCu, while the amorphous interphase is mainly composed of metallic oxides. As already stated, the nanosheet is a chemicallycomplex nanostructured cermet that comprises metallic nanocrystals, which are encircled by amorphous oxides in the presence ofsome residuals of the decomposed PVA.

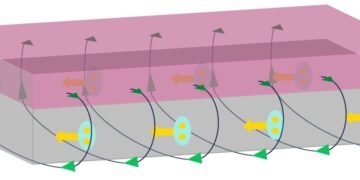

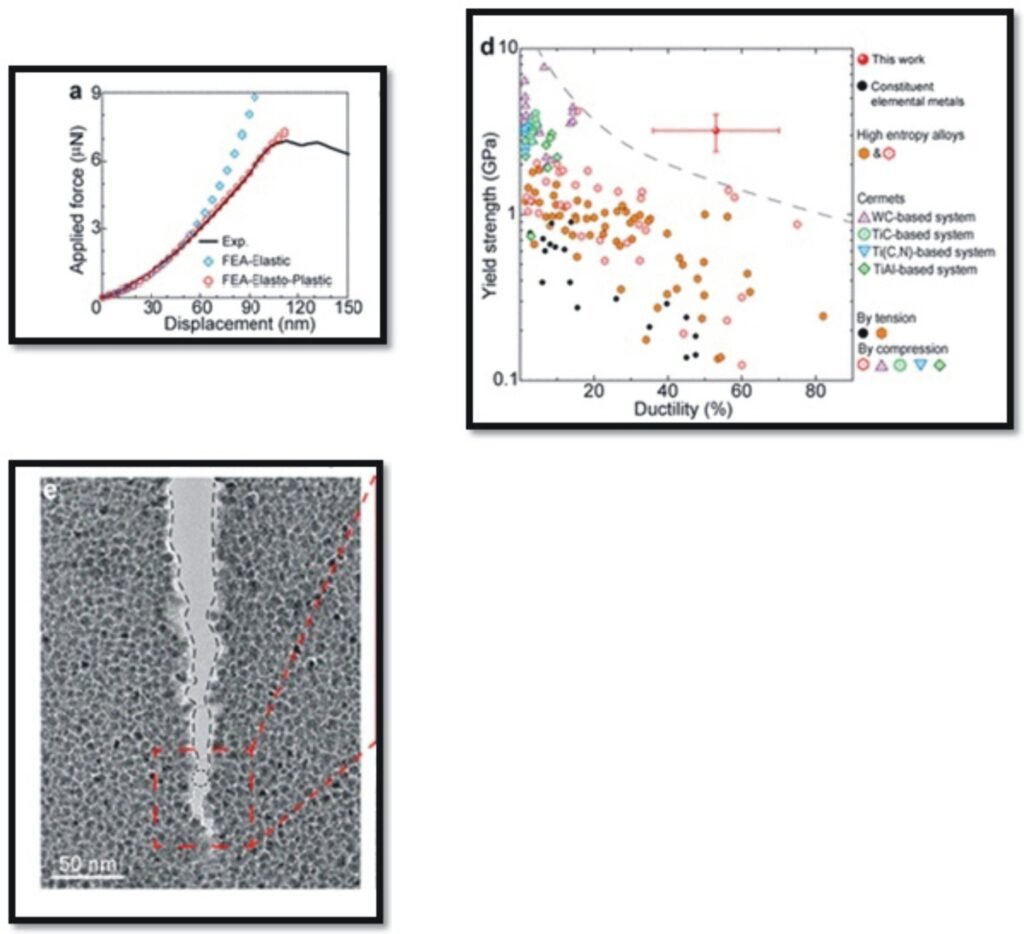

Figure-3: Mechanical and thermal behaviour of the freestanding cermet nanosheet. (a) The experimental force−displacement curve of a 20 nm-thick cermet nanosheet under AFM indentation in comparison with the FEA simulations. (d) The plot of yield strength versus ductility for our HEA derived cermet in comparison with other metals and cermets. (e) TEM image of the arrested crack in the 20 nm-thick cermet nanosheet.

“Reprinted with permission from {Strong yet Ductile High Entropy Alloy Derived Nanostructured Cermet, Jingyang Zhang, Qing Yu, Qing Wang, et al, Nano Letters}. Copyright {Sep. 1 2022) American Chemical Society.”

AS conducted in the previous studies (Measurement of the Elastic Properties and Intrinsic Strength of Monolayer Graphene), the elastic properties and intrinsic breaking strength of freestanding cermet nanosheets was measured through atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanoindentation in an atomic force microscope. In addition, finite element analysis (FEA) was also carried out. Figure 3 (a) shows a typical force−displacement plot obtained from the 20 nm-thick cermet nanosheet.

The researchers have obtained through data fitting, a yield strength of 3.2 ± 0.73 GPa and an elastic modulus of 177 ± 27.9 GPa for the cermet nanosheets with a strain hardening modulus of 0.01 GPa. Moreover, it is of interest to note, the force−displacement curve (Figure 3a) suggests that in the present case, cermet nanosheet deformed plastically as well. The FEA analysis studies revealed that the cermetnanosheet could withstand a substantial plastic strain after yielding,which can reach 53 ± 17.1% in terms of von Mises strainbefore mechanical softening. Such a unique synergistic combination of strength -ductility behaviour very rarely occurs in the cermet.

As displayed in Figure 3 (d) a comparison has been made between the cermet nanosheets (as referred in the present case) with their constituent elemental metals, namely, Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu; bulk HEAs, WC, TiC, Ti (C, N); and TiAlbaed systems with respect to their strength and ductility. Undoubtedly, one can clearly see that these cermet nanosheets surpass all the above-mentioned metals and cermets in terms of both high strength and high ductility. Figure 3 (e) exhibits the arrested main crack in the cermet nanosheet; thecrack bridging, crack tip blunting, and deflection observed here implies that the crack propagation occurs byductile fracture. Given a crack-tip opening displacement of >15nm (as mentioned in this paper), one can estimate the fracture toughness of our cermet is estimated to be>50 J/m2 following the prior work (Plane strain deformation near a crack tip in a power-law hardening material).

Considering the ultrathinthickness of the nanosheet (20−30 nm) referred in this study, this toughness is spectacular in its magnitude. Further examination (although not shown here in the figure) at higher magnification of the crack revealed in order tobridge thecrack, the nanosized amorphous interphase is stretched by100% to 500% despite its oxide nature. This outstanding stretchability is astonishing and akin to the liquid-likebehaviour of nanoscale metallic glasses (MGs) observed in insitu TEM experiments (Super elongation and Atomic Chain Formation in Nanosized Metallic Glass).

To understand the atomic origin of plasticity the researchers carried out detailed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and it was concludedthat in their cermet plasticity arises mainly due to compliant nature of the amorphous interphase, and the atomic rearrangement which takes place around the nanocrystal; in addition, elastic confinement in this distinctive nanostructure contributes to strain hardening that is necessary for achieving the uniform strain, or the ductility displayed for their cermet.The ultrathin ceramet developed in the present study have great potential due to their outstanding mechanical and physical properties for the next generation electronic devices where flexibility is an additional requirement.

Currently, the cermet developed by the researchers are very thin in nature, however, it is feasible to assemble them into bulk layered bodies by employing additional fabrication techniques such as reported in the literature (AuAgNanosheets Assembled from Ultrathin AuAg Nanowires and Fast Surface Dynamics Enabled Cold Joining of Metallic Glasses).

Concluding Remarks

“Reprinted with permission from {Strong yet Ductile High Entropy Alloy Derived

Nanostructured Cermet, Jingyang Zhang, Qing Yu, Qing Wang, et al, Nano Letters}.

Copyright {Sep. 1 2022) American Chemical Society.”

To Summarize, in the present work ((Strong yet Ductile High Entropy Alloy Derived Nanostructured Cermet), the researchers synthesized a strong yet ductile freestanding ultrathin cermet by reacting high entropy alloy nanocrystals with the three-dimensional molecular structure of hydrogels. This reaction results in a unique nanostructure comprising metallic nanocrystals surrounded by a complex amorphous oxides interphase having a rather low glass transition point, which endows it with very high stretchability of up to 500%. This distinct nanostructure results in an outstanding combination of strength (3.2 GPa) and ductility (>50%), which surpasses bulk as well as thin-film cermets as reported in the literature in recent times.

Molecular Dynamics studies disclose that the unprecedent ductility observed in this work possibly arises from the deformation occurring at the amorphous-crystal interface in addition to the elastic restraint imposed by the nanostructure on the amorphous interphase. These superb mechanical properties, ultrathin thickness, and high aspect ratio make high entropy alloy derived cermet an ideal candidate for the next-generation nanomechanical resonators and conformable flexible electronics.

About Author

Dr Yashwant R Mahajan was Technical Advisor at International Advanced Research Centre for Powder Metallurgy and New Materials (ARCI), Hyderabad. He obtained his Ph.D. degree in PhysicalMetallurgy in 1978 from Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, New York. He has worked in variouscapacities, namely, Scientist/Joint Director at the Defence Metallurgical Research Laboratory, ARCI,and Defence Research and Development Laboratory, Hyderabad, India, and Hindustan AeronauticsLtd., Bangalore, India. Dr Mahajan made major contributions in the areas of MMCs, advancedceramics, and CMCs. Under his leadership, a number of ceramic- based technologies weredeveloped and transferred to the industry. He has published more than 130+ technical papers inpeer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings and holds 13 patents (including 2 US). DrMahajan had initiated and successfully implemented a number of programs concerning selectionand application of advanced materials for defence applications, which includes Development ofInfrared Domes and Windows Based on Transparent Ceramics, SiAlONRadomes for HypersonicMissile Applications, Ultra-High Temperature Materials for the Airframe and Scramjet Engine ofHypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle, Reaction Bonded Silicon Carbide Thrust Bearings forNaval Application, and Silicon Carbide Based Mirror Substrates for Satellite Application.

He is presently Editorial Advisor to Nano Digest. Email: mahajanyrm@gmail.com