The advent of inexpensive wearable sensors that can monitor heart rate and body temperature, as well as levels of blood sugar and metabolic byproducts, has allowed researchers and health professionals to monitor human health in ways never before possible. But like all electronic devices, these wearable sensors need a source of power. Batteries are an option, but are not necessarily ideal because they can be bulky, heavy, and run out of charge.

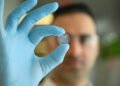

Caltech’s Wei Gao, assistant professor of medical engineering in the Andrew and Peggy Cherng Department of Medical Engineering, has been developing these sensors as well as novel approaches to power them using the human body itself. Previously, he created a sensor that could monitor health indicators in human sweat that is powered by sweat itself.

Now, Gao has developed a new way to power wireless wearable sensors: He harvests kinetic energy that is produced by a person as they move around.

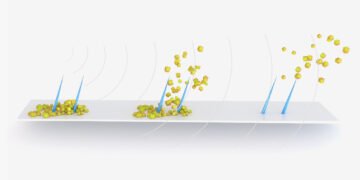

This energy harvesting is done with a thin sandwich of materials (Teflon, copper, and polyimide) that are attached to the person’s skin. As the person moves, these sheets of material rub against a sliding layer made of copper and polyimide, and generate small amounts of electricity. The effect, known as triboelectricity, is perhaps best illustrated by the static electric shock a person might receive after walking across a carpeted floor and then touching a metal doorknob.

“Our triboelectric generator, also called a nanogenerator, has a stator, which is fixed to the torso, and a slider, which is attached to the inside of the arm. The slider slides against the stator during human motion, and, an electrical current is generated at the same time,” Gao says. “The mechanism is quite simple. Friction results in electrical generation. This is not something new, concept-wise.”

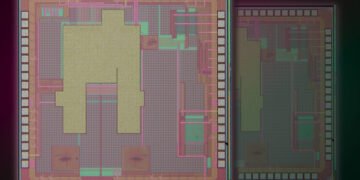

What is new, Gao says, is how the research team manufactured the nanogenerator.

“Instead of using fancy materials, we use commercially available flexible circuit boards,” he says. “This material is cheap and very durable and mechanically robust over long periods of time.”

The nanogenerator does not create a lot of electricity; indeed, one would need a device with 100 square meters of surface area to power a 40-watt light bulb. However, Gao’s wearable sensors have low power requirements, and the system stores up generated electricity in a capacitor until there is enough charge to take a reading from the sensor and wirelessly send the data to a cell phone through Bluetooth. The more a person moves, the more often the sensor can collect data. Even if the person is fairly sedentary, however, the sensor eventually will accumulate enough power to operate.

Gao ultimately would like to run his wearable sensors using power that is generated through multiple methods. For example, a wearable device might use electricity generated from sweat, a triboelectric generator, and small wearable solar panels.

The paper describing the research, titled, “Wireless battery-free wearable sweat sensor powered by human motion,” appears in Issue 40 of the journal Science Advances.