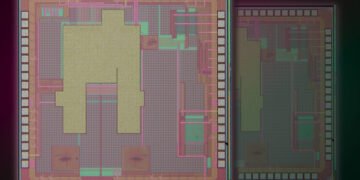

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have now adapted a low-cost optical method of examining the shape of small objects so that it can detect certain types of nanocontaminants smaller than 25 nanometers (nm) in height—about the size of a small virus. The technique could easily be incorporated into the manufacturing process for semiconductor devices, said NIST researcher Kiran Attota.

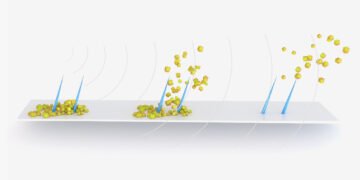

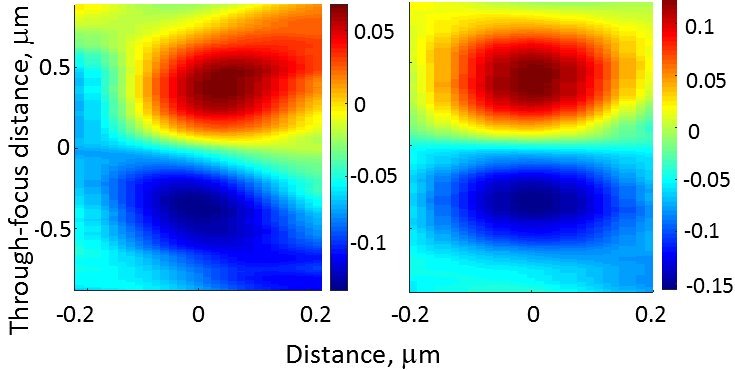

At NIST, Attota helped pioneer the method, known as Through-Focus Scanning Optical Microscopy (TSOM), about 15 years ago. TSOM transforms a conventional, inexpensive optical microscope into a powerful three-dimensional shape-measuring tool at the nanometer scale. Instead of recording a single, sharp image when a sample lies at a fixed distance from the lens, the microscope takes several out-of-focus, two-dimensional images, each with the sample at a different distance from the instrument and source of illumination. (Collectively, these images contain much more information than does a single in-focus image.)

A computer then extracts the variation in brightness—the so-called brightness profile—across each image. Each brightness profile is different because for each image, the sample resides at a different distance from the light source. Combining these two-dimensional profiles, the computer constructs a finely detailed, three-dimensional image of the sample.

Indeed, Attota and his colleagues originally developed the technique to record the full three-dimensional shape of small objects, not to detect nanocontaminants. But by optimizing both the wavelength of the light source and the alignment of the microscope, the team produced TSOM images with the high sensitivity required to reveal the presence of nanocontaminants in a small sample of semiconductor material.

Because the optimized TSOM method does not require costly equipment and can image samples in real time, the technique is ready to be adopted by manufacturers, Attota noted.