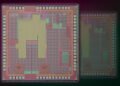

(Using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to identify fat (white) in the body, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found excessive fat in a mouse that had consumed a high-fat diet for six weeks (left). The mouse on the right ate the same diet, but the researchers blocked the activity of a gene in specific immune cells, resulting in that mouse not becoming obese.)

Disabling a gene in specific mouse cells, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have prevented mice from becoming obese, even after the animals had been fed a high-fat diet.

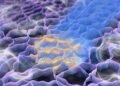

The researchers blocked the activity of a gene in immune cells. Because these immune cells — called macrophages — are key inflammatory cells and because obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, the researchers believe that reducing inflammation may help regulate weight gain and obesity.

The study is published May 1 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“We’ve developed a proof of concept here that you can regulate weight gain by modulating the activity of these inflammatory cells,” said principal investigator Steven L. Teitelbaum, MD, the Wilma and Roswell Messing Professor of Pathology & Immunology. “It might work in a number of ways, but we believe it may be possible to control obesity and the complications of obesity by better regulating inflammation.”

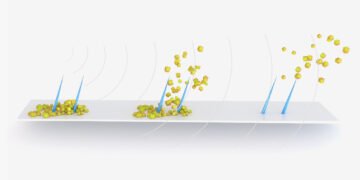

When people are obese, they burn fewer calories than those who are not obese. The same is true for mice. But according to co-first author Wei Zou, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pathology & immunology, the researchers found that obese mice maintained the same level of calorie burning as mice that were not obese — after the research team deleted the ASXL2 gene in the macrophages of the obese mice and, in a second set of experiments, after they injected the animals with nanoparticles that interfere with the gene’s activity.

Despite high-fat diets, the treated animals burned 45% more calories than their obese littermates with a functioning gene in macrophages.

Exactly why this prevented obesity in the mice isn’t clear. Co-first author Nidhi Rohatgi, PhD, an instructor in pathology, said it appears to involve getting white fat cells — which store the fat that makes us obese — to behave more like brown fat cells — which help to burn stored fat. The strategy is a long way from becoming a therapy, but it has the potential to help obese people burn fat at rates similar to rates seen in lean people.

“A large percentage of Americans now have fatty livers, and one reason is that their fat depots cannot take up the fat they eat, so it has to go someplace else,” Teitelbaum said. “These mice consumed high-fat diets, but they didn’t get fatty livers. They don’t get type 2 diabetes. It seems that limiting the inflammatory effects of their macrophages allows them to burn more fat, which keeps them leaner and healthier.”