A thin 2-D nanomaterial of hexagonal boron nitride is a key component of a cost-effective technology developed by Rice University engineers for the desalination of industrial brine.

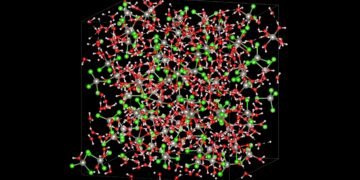

More than 1.8 billion people live in countries where there is a shortage of freshwater. In many arid areas, seawater or saltwater groundwater is sufficient, but its desalination is expensive. In addition, many industries pay high costs for the disposal of high-salt waste that cannot be treated by conventional technologies. Reverse osmosis, the most common desalination technology, requires increasing pressure with increasing salinity of the water and cannot be used to treat water that is too salty or hypersaline. Hypersalted water, which can contain 10 times more salt than seawater, is an even more important challenge for many industries. Other oil and gas wells, for example, produce it in large quantities and is a by-product of many desalination technologies that produce fresh water and concentrated brine. According to Qilin Li of Rice, co-author of a study on rice desalination technology published in Nature Nanotechnology, the driving force is also raising water awareness in every industry.

“It’s not just the oil sector,” said Li, co-director of the Rice-Based Water Technology Center for Nanotechnology (NEWT). “Industrial processes generally produce salt waste because the trend is water reuse. Many industries are trying to have a “closed-loop” water system. Each time you restore (2-D nanomaterial of hexagonal boron nitride) freshwater, the salt becomes more concentrated. Eventually, the wastewater will become hypersoluble and you will have to desalinate it or pay to remove it. ”

Conventional hypersolence desalination technology has high investment costs and requires a large infrastructure. NEWT, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Engineering Research Center (NSF), based at Rice’s Brown School of Engineering, uses the latest advances in nanotechnology and materials science to streamline decentralized, appropriate target technologies for drinking water and industrial wastewater treatment. .

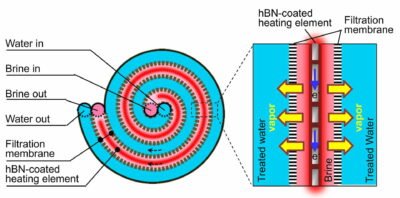

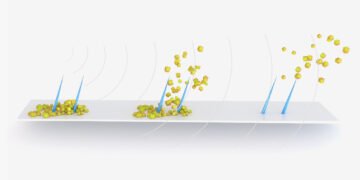

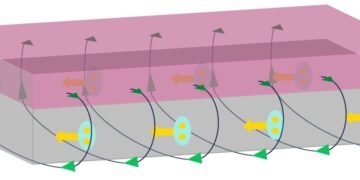

One of NEWT’s technologies is an off-grid desalination system that uses solar energy and a process called membrane distillation. As the saline solution flows along one side of the porous membrane, it is heated on the surface of the membrane by a photothermal coating that absorbs sunlight and generates heat. As cold flat water flows to the other side of the membrane, the temperature difference creates a pressure gradient that pushes water vapor across the membrane from the warm to the cold side, leaving salt and other non-volatile impurities behind.

The large temperature difference on both sides of the membrane is the key to better desalination of the membrane. In the solar-powered version of NEWT technology, the light-activated nanoparticles attached to the membrane obtain all the necessary energy from the sun, which results in high energy efficiency. Li worked with industrial partner NEWT to create a version of the technology that could be deployed for humanitarian purposes. But unconcentrated solar energy alone is not enough to desalinate hypersolence brine quickly, he said.

“Energy efficiency is limited to the surrounding solar energy,” said Li, a professor of civil and environmental engineering. “The power consumption (2-D nanomaterial of hexagonal boron nitride) is only one kilowatt per square meter and the speed of water production is slow in large systems.”

Increasing the surface heat of the membrane can cause an exponential increase in the amount of freshwater that each square foot of membrane can produce per minute, a measure known as flow. However, saltwater is extremely harmful and can be even more harmful when heated. Traditional metal heating elements break down quickly and many non-metallic alternatives are better or do not have sufficient conductivity. “We’re really looking for a material that’s more electrically conductive and also supports a high current density that doesn’t rot in this very salty water,” Li said.

Colleagues Jun Lou and Pulickel Ajayan of Rice’s Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering (MSNE) came up with the solution. Postdoctoral researchers Lou, Ajayan, and NEWT and study co-authors Kuichang Zuo and Weipeng Wang and study co-author and graduate student Shuai Jia performed the process of coating a fine stainless steel mesh with a thin film of hexagonal boron nitride (hBN).

Due to the combination of chemical resistance and thermal conductivity of boron nitride, its ceramic shape is an expensive accessory in high-temperature equipment, but hBN, a 2D atomic material, is usually grown on flat surfaces.

“This is the first time this beautiful hBN coating has grown on an irregular, porous surface,” Li said. “It’s a challenge because wherever you have a defect in the hBN coating, you’re starting to corrode.”

Jia and Wang used a modified chemical vapor deposition (CVD) technique to grow dozens of layers of hBN in an untreated, commercially available stainless steel mesh. This technique extends Rice’s previous research into the growth of 2-D materials on curved surfaces, supported by the ATOMIC Center for Atomic Thin Multifunction Coatings. ATOMIC is also run by Rice and supported by the NSF Industrial / University Research Program.

The researchers have shown that a wire mesh coating just 10 million meters thick is sufficient to coat the coated wires and protect them from the harmful forces of hypersaline water. . The coated wire mesh heating element is enclosed by a commercially available polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in a spiral wound module, which is a space-saving form used in many commercial filters. In the tests, the scientists supplied the heater with a domestic frequency voltage of 50 Hz and a power density of up to 50 kilowatts per square meter. At maximum output, the system produces a flow of more than 42 kilograms of water per square meter of membrane per hour – more than 10 times greater than the surrounding solar membrane distillation technology – with energy efficiency higher than the current membrane distillation technology.

Li said the team was looking for an industrial partner to scale the CVD coating process and create a larger prototype for small field trials.

“We are ready to continue some commercial applications,” he said. “Scaling the lab process to a large 2-D CVD blade will require external support.”