An interdisciplinary research group from the Institutes of Physical Chemistry and Physics of the University of Freiburg and the Max Planck Institute for Biophysics in Frankfurt am Main has discovered a new tension based on the direction in proteins called Anisotropic friction Discovered

“Until now, no one has noticed that the friction in biomolecules depends on the direction,” says scientist Dr Steffen Wolf of the University of Freiburg. The results were published on the cover of the scientific journal “Nano Letters”.

Analysis and model of the protein-ligand complex

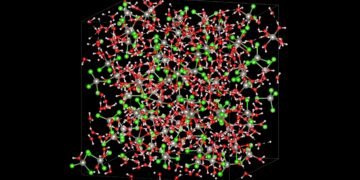

Proteins are microscopic molecules of cells. They work during their working hours. As a result, they follow the laws of thermodynamics, exhibit energy conversion efficiency, and lose energy during their work process due to resistance. From a macroscopic point of view, this last effect corresponds to an apparent contradiction. On the microscopic scale of individual proteins, the most prominent source of friction is the internal protein friction resulting from the excitation of internal protein vibrations. Another source is melt friction, which results from the acceleration of surrounding melt particles. These friction points cause both the protein and the solvent to heat up. Here, the researchers discovered the new type of conflict by performing single-molecule analysis and simulations in the complex of proteins and ligands.

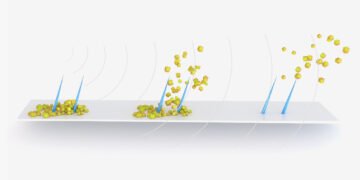

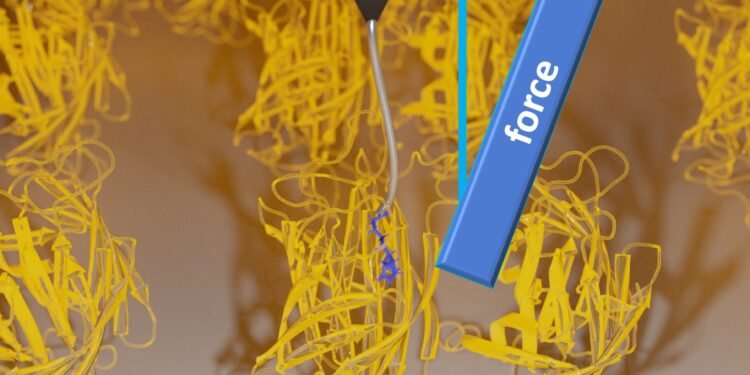

In their single-molecule analysis, the team used a new technique that applies stereographic force spectroscopy to single molecules, based on atomic force microscopy (AFM). This method allowed them to study the dissociation of the ligand from the surface protein not only in one configuration, but also in the Cartesian three-dimensional configuration. During their experiment, Dr Wanhao Cai, Professor Dr Thorsten Hugel and Dr Bizan N. Balzer from the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the University of Freiburg with Dr. Jakob T. Bullerjahn from the Max Planck Institute, made a surprising discovery that the tension during ligand separation increases with the angle of attraction applied.

Combines experiments with computer simulations

Miriam Jäger and Dr Steffen Wolf from the Institute of Physics at the University of Freiburg then replicated the experiment using computer simulations. They use high-performance computing (HPC) facilities from the BinAC-HPC-Cluster in Tübingen. During the simulations, they determined that the function of removing the ligand from its binding site depends on the correct direction of application of the pulling force.

By combining the experimental results with the simulations, the researchers realized that the source of the friction depends on the angle is the unexplained and random distortion of the proteins along their surface axes. turn to the experiment. The team repeated the single-molecule extraction experiment by binding and unbinding the ligand to and from the protein several times to obtain the most obvious results. There, the ligand binds to different proteins for each size. Therefore, in each measurement, the ligand is placed in one part on the surface, but in different areas of the protein depending on it. This orientation cannot be defined, both in experimental setups and in the real world, and no exact measurements can be repeated in the orientation. Therefore, each time, a different force is applied to the biomolecule. An irreversible part of the energy is lost as heat and process. The corresponding effect is a source of friction, which researchers call anisotropic friction.

Basic types of conflict

“We think that this previously unknown and fundamental conflict exists in any bioassembly in which the structure of proteins arises in the direction of energy,” said Dr. Bizan N says. Balzer, a biophysicist. He explains that this is something in the biomolecular motors or membrane proteins that force the force, and in systems like blood flow, where the force is applied to the proteins that depend on it. Balzer concluded: “Anisotropic properties are another important factor of complexity for understanding friction in engineering applications and in living things in general.”

Source: University of Freiburg