A team of engineers at CU Boulder has developed a new class of tiny moving robots (A small robot with its own hands) that can transport liquids at breakneck speeds and can deliver prescription drugs in a day to hard-to-reach places in the human body. .

The researchers describe their small health care providers in an article published last month in the journal Small.

“Imagine if microrobots can perform certain tasks in the body, such as non-invasive surgery,” said Jin Lee, who led the study and is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering. “Instead of cutting the patient open, we can introduce robots into the body through pills or injections, and they will perform the procedure themselves.”

Lee’s colleagues weren’t there, but this new research is a big step forward for tiny robots.

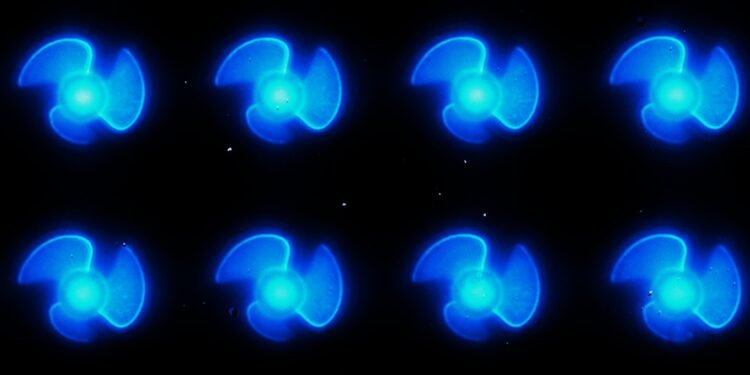

The microrobot of the group is really small. Each is only 20 micrometers in diameter, many times smaller than the width of a human hair. They are also very fast, able to move at a speed of about 3 millimeters per second, or about 9,000 times their own length per second. He runs several times faster than a cheetah in terms of speech.

They also have great potential. In this new study, the team deployed a fleet of these machines to deliver doses of dexamethasone, a common steroid, into the intestines of lab mice. The results show that microrobots can be a useful tool for treating gastrointestinal and other diseases in humans.

“Microscale robots have generated a lot of excitement in the scientific community, but what makes them interesting to us is that we can design them to perform useful functions in the body,” C. Wyatt Shields, author of the new study and assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering.

A wonderful journey

If it sounds straight out of science fiction, that’s because it is. In the famous film Fantastic Voyage, a group of adventurers travel from a wrecked submarine to the body of a comatose man.

“The film was released in 1966. Today, we live in the era of microscale and nanoscale robots,” Lee said.

He thinks that, as in the film, microrobots can circulate in human blood, looking for the desired place to treat various diseases.

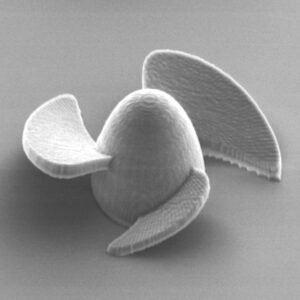

The team makes their microrobots from materials called biocompatible polymers using a technology similar to 3D printing. The machines look like small rockets and come with three small fins. They also include a little something else: each of the robots carries a small trapped air bubble, like what happens when you dip a glass face in water.

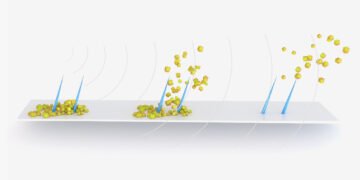

If you expose the machines to a field of music, like the one used in ultrasound, the bubbles will start to vibrate a lot, moving the water and lifting the robots forward.

Other CU Boulder co-authors of the new study include Nick Bottenus, assistant professor of mechanical engineering; Ankur Gupta, Assistant Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering; and engineering graduate students Ritu Raj, Cooper Thome, Nicole Day and Payton Martinez.

To test their microrobots, the researchers focused on a common human problem: bowel disease.

Bring help

Interstitial cystitis, also known as painful bladder disease, affects millions of Americans and, as the name suggests, can cause severe pelvic pain. Treating the disease can be uncomfortable. Often, patients will go to the clinic several times a week where the doctor will use a catheter to inject a strong solution of dexamethasone into the intestines.

Lee thinks microbots can provide some relief.

In a laboratory study, the researchers created a school of microrobots that produced high concentrations of dexamethasone. They introduced thousands of these robots into the intestines of lab mice. The result is a truly living journey: the microbots are scattered around the body before they stick to the wall of the bladder, which can make them difficult to absorb.

Once they arrived, the machines slowly released their dexamethasone for about two days. Such continuous medications can allow patients to receive other medications over a longer period of time, Lee said, improving patient outcomes.

He added that the team has a lot of work to do before the microbots can actually travel through the human body. For starters, the team wanted to make the machines biodegradable enough to eventually dissolve in the body.

“If we can make the molecules work in the bladder,” Lee said, “then we can get a sustained drug release, and maybe patients won’t come to “hospital often.”

Source: University of Colorado Boulder.