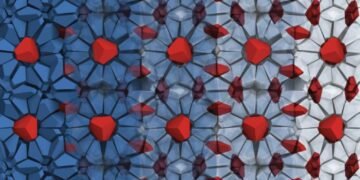

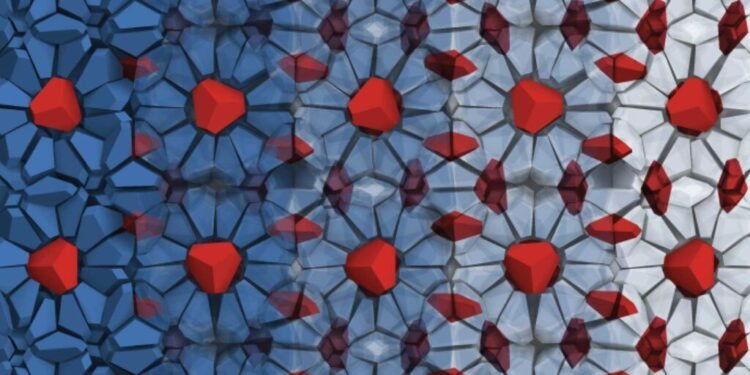

Crafting the “fire ice” structure with nanoparticles, The structure exploits a strange physical phenomenon and could allow engineers to manipulate light in new ways.

Cage structures made with nanoparticles could be a route to making organized nanostructures with mixed materials, and researchers at the University of Michigan have shown how to achieve this through computer simulations. The discovery (Crafting the “Fire Ice” Structure with Nanoparticles) could open new avenues for photonic materials that manipulate light in ways that natural crystals cannot. It also showed a special effect the team called entropy compartmentalization. Sharon Glotzer, director of chemical engineering at Anthony C. Lembke, who led the project, said: “We are creating new ways to process materials across scales, revealing our possibilities and strengths. can be used.” “Entropic forces can make crystals more complex than we thought.”

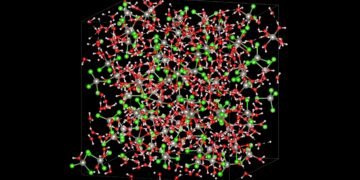

Although entropy is often described as disorder in a system, it more accurately reflects the process of a system that maximizes its potential state. Most of the time, it ends in chaos. Oxygen molecules don’t stick together, they spread out to fill the room. And if you put them in the right size box, they will naturally order themselves into a recognizable structure.

Nanoparticles do the same thing. Earlier, Glotzer’s team had shown that bipyramid particles – like two short pyramids, with three sides joined at their base – would form a solid like ice if you put them in a small box full of ice. limit. Methane is surrounded by water molecules, and it can burn and melt at the same time. This material is found in abundance at the bottom of the ocean and is an example of a clathrate. Clathrate structures are being investigated for various applications, such as trapping and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

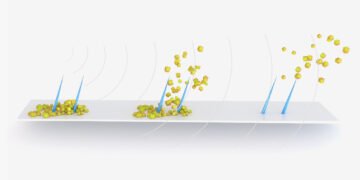

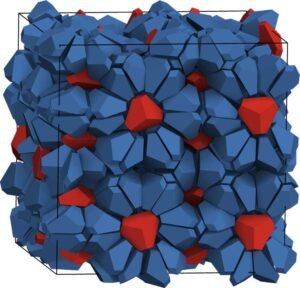

Unlike water clathrates, previous nanoparticle clathrate structures do not have holes to fill with other materials that can provide new and exciting opportunities to modify the properties of the structure. The team wants to change this.

In modern times, we studied it if we change the nature of the particle. “We thought that if we moved the particle a little bit, it would create a hole in the room made by the bipyramid particles,” said Sangmin Lee, a recent PhD graduate in chemical engineering and first author of the paper. said the body.

He removed the three parts in the center of each bipyramid and found a sweet spot where holes appeared in the structure, but the parts of the pyramid were still intact so that they did not start to arrange themselves in a different way. The spaces are filled with other broken bipyramids when they are the only elements in the system. When the second shape was added, that shape became a trapped guest particle. Glotzer has an idea about how to choose the right side of the adhesive that will allow different things to act as cages and host things, but in this case, there is no glue that connects the bipyramids together. Instead, entropy supported the structure entirely.

“What’s really interesting, looking at the simulations, is that the host lattice is almost frozen. The host elements are moving, but they all come together as one. strong, which is exactly what happens in water clathrates,” said Glotzer. “But the host particles are spinning like crazy, as the process throws all the entropy into the host element.”

It is a system with degrees of freedom that a truncated bipyramid can build in a small space, but almost all of the freedom is owned by hosts. Methane and water clathrates are also circulating, the researchers said. What’s more, when they removed the guest particles, the structure threw bipyramids that had been part of the networked cage structure into the cage interiors—it was more important to have spinning particles available to maximize the entropy than to have complete cages.

“Entropy compartmentalization. Isn’t that nice? I bet it happens in other systems, not just clathrates,” Glotzer said.

Source: University of Michigan