Ultrathin materials such as graphene promise a revolution in nanoscience and technology. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have now made an important advance within the field. In a recent paper in Nature Communications they present a method for controlling the edges of two-dimensional materials using a ‘magic’ chemical.

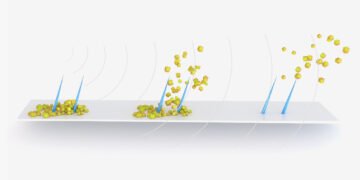

“Our method makes it possible to control the edges — atom by atom — in a way that is both easy and scalable, using only mild heating together with abundant, environmentally friendly chemicals, such as hydrogen peroxide,” says Battulga Munkhbat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Physics at Chalmers University of Technology, and first author of the paper.

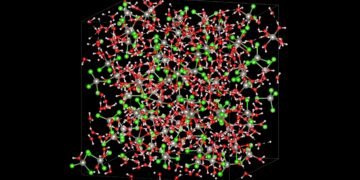

Materials as thin as just a single atomic layer are known as two-dimensional, or 2D, materials. The most well-known example is graphene, as well as molybdenum disulphide, its semiconductor analogue. Future developments within the field could benefit from studying one particular characteristic inherent to such materials — their edges. Controlling the edges is a challenging scientific problem, because they are very different in comparison to the main body of a 2D material. For example, a specific type of edge found in transition metal dichalcogenides (known as TMD’s, such as the aforementioned molybdenum disulphide), can have magnetic and catalytic properties.

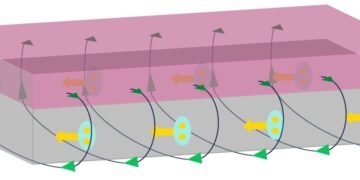

Typical TMD materials have edges which can exist in two distinct variants, known as zigzag or armchair. These alternatives are so different that their physical and chemical properties are not at all alike. For instance, calculations predict that zigzag edges are metallic and ferromagnetic, whereas armchair edges are semiconducting and non-magnetic. Similar to these remarkable variations in physical properties, one could expect that chemical properties of zigzag and armchair edges are also very different. If so, it could be possible that certain chemicals might ‘dissolve’ armchair edges, while leaving zigzag ones unaffected.

“Our method makes it possible to control the edges — atom by atom — in a way that is both easy and scalable, using only mild heating together with abundant, environmentally friendly chemicals, such as hydrogen peroxide,” says Battulga Munkhbat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Physics at Chalmers University of Technology, and first author of the paper.

Ultrathin materials such as graphene promise a revolution in nanoscience and technology. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have now made an important advance within the field. In a recent paper in Nature Communications they present a method for controlling the edges of two-dimensional materials using a ‘magic’ chemical.

“Our method makes it possible to control the edges — atom by atom — in a way that is both easy and scalable, using only mild heating together with abundant, environmentally friendly chemicals, such as hydrogen peroxide,” says Battulga Munkhbat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Physics at Chalmers University of Technology, and first author of the paper.

Materials as thin as just a single atomic layer are known as two-dimensional, or 2D, materials. The most well-known example is graphene, as well as molybdenum disulphide, its semiconductor analogue. Future developments within the field could benefit from studying one particular characteristic inherent to such materials — their edges. Controlling the edges is a challenging scientific problem, because they are very different in comparison to the main body of a 2D material. For example, a specific type of edge found in transition metal dichalcogenides (known as TMD’s, such as the aforementioned molybdenum disulphide), can have magnetic and catalytic properties.

Typical TMD materials have edges which can exist in two distinct variants, known as zigzag or armchair. These alternatives are so different that their physical and chemical properties are not at all alike. For instance, calculations predict that zigzag edges are metallic and ferromagnetic, whereas armchair edges are semiconducting and non-magnetic. Similar to these remarkable variations in physical properties, one could expect that chemical properties of zigzag and armchair edges are also very different. If so, it could be possible that certain chemicals might ‘dissolve’ armchair edges, while leaving zigzag ones unaffected.

“Our method makes it possible to control the edges — atom by atom — in a way that is both easy and scalable, using only mild heating together with abundant, environmentally friendly chemicals, such as hydrogen peroxide,” says Battulga Munkhbat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Physics at Chalmers University of Technology, and first author of the paper.