The research, published in Environmental Science & Technology, showed that most of the microplastics exposed in Auckland’s air are small in size, raising concerns about the ability to breathe and accumulate in the human body.

Researchers at the University of Auckland have calculated that 74 metric tons of microplastics fall into the city from the air each year, with more than 3 million plastic bottles falling from the sky.

According to lead author Dr Joel Rindelaub, of the School of Chemical Sciences at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, researchers around the world can dramatically underestimate airborne microplastics.

Levels in Auckland’s air are several times higher than those recorded in London, Hamburg and Paris in recent years, as scientists in the new study used sophisticated chemical methods to detect and analyze microscopic particles. to 0.01 millimeters.

The average (mean) number of airborne microplastics inhaled per square meter per day is 4,885. This compares to 771 in London (reported in a survey published in 2020), 275 in Hamburg (2019) and 110 in Paris (2016).

“Future work should clarify exactly which plastics we breathe,” says Dr Rindelaub. “It’s becoming increasingly clear that this is an important avenue of disclosure.”

This study is the first to quantify the concentration of microplastics in the city’s air.

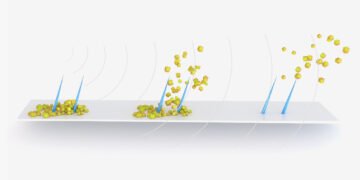

Breaking waves in the Hauraki Strait may play an important role in Auckland’s problem by transporting waterborne microplastics into the air.

This effect appears to be at work when Rindelaub and his colleagues, including PhD student Wenxia Fan and Professor Jennifer Salmond, recorded an increase in the number of waves when the ocean winds picked up speed, possibly carrying large waves and transmissions.

“The production of airborne microplastics from breaking waves may be a major part of the global microplastics movement,” says Rindelaub. “That could help explain how some microplastics get into the atmosphere and are transported far away, like here in New Zealand.”

The particle size changes with the direction of the wind. When the wind passes through downtown Auckland, the microplastics in the air are large, indicating that the plastic has not aged in the environment and came from nearby.

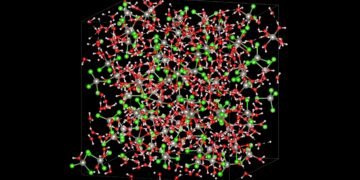

Polyethylene (PE) is the main material identified, followed by polycarbonate (PC) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polyethylene and PET are packaging materials where PC is used in electrical and electronic equipment. All three are also used in the construction industry.

In the study, airborne microplastics were captured from pits and pots in wooden boxes on the roof of the city’s central university campus. The same arrangement is in the residential complex in Remuera.

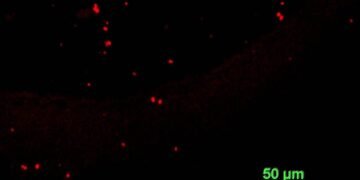

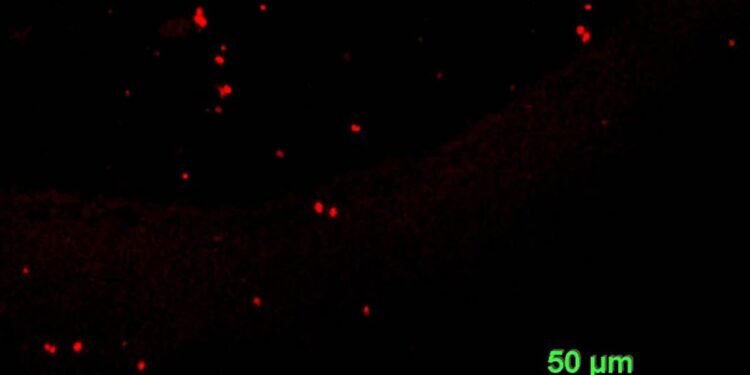

Almost all microplastics are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Scientists discovered the smallest particles by applying a dye that emits light under certain conditions. Heat treatment is used to check the size. Rindelaub says,

“The more we look at the size, the more we see microplastics. “This is significant because the smallest size is the most toxicologically.”

Nanoplastics, the smallest, have the ability to enter cells, cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in organs such as the testicles, liver and brain. “Microplastics have also been found in human lungs and in the tissues of cancer patients, indicating that the inhalation of airborne microplastics poses a risk to humans,” the paper says. Plastic was also found in the placenta.

This paper, written by Professor Kim Dirks, Dr Patricia Cabedo Sanz and Professor Gordon Miskelly, calls for the standardization of metrics to be used to compare the study of microplastics air.

The preface of the book says: “Over the past 70 years, 8.3 billion pieces of plastic have been produced worldwide. Only nine percent were recycled, while the rest were incinerated or released into the environment.

Fibers scattered from washing synthetic clothes, pieces of car tires thrown in the rain and washed into the ocean, and bottles floating on the beach are just a few of the ways that plastic is added to the ‘ around. Weathering and aging breaks down rubber into small particles.

The experiment took place over nine weeks in September, October and November 2020.