Scientists at Osaka University develop a label-free method for identifying respiratory viruses based on changes in electrical current when they pass through silicon nanopores, which may lead to new rapid COVID-19 tests.

The ongoing global pandemic has created an urgent need for rapid tests that can diagnose the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the pathogen that causes COVID-19, and distinguish it from other respiratory viruses. Now, researchers from Japan have demonstrated a new system for single-virion identification of common respiratory pathogens using a machine learning algorithm trained on changes in current across silicon nanopores. This work may lead to fast and accurate screening tests for diseases like COVID-19 and influenza.

In a study published this month in ACS Sensors scientists at Osaka University have introduced a new system using silicon nanopores sensitive enough to detect even a single virus particle when coupled with a machine learning algorithm.

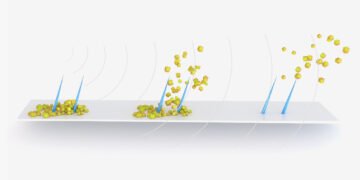

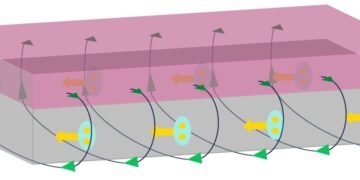

In this method, a silicon nitride layer just 50 nm thick suspended on a silicon wafer has tiny nanopores added, which are themselves only 300 nm in diameter. When a voltage difference is applied to the solution on either side of the wafer, ions travel through the nanopores in a process called electrophoresis.

The motion of the ions can be monitored by the current they generate, and when a viral particle enters a nanopore, it blocks some of the ions from passing through, leading to a transient dip in current. Each dip reflects the physical properties of the particle, such as volume, surface charge, and shape, so they can be used to identify the kind of virus.

The natural variation in the physical properties of virus particles had previously hindered implementation of this approach, however, using machine learning, the team built a classification algorithm trained with signals from known viruses to determine the identity of new samples. “By combining single-particle nanopore sensing with artificial intelligence, we were able to achieve highly accurate identification of multiple viral species,” explains senior author Makusu Tsutsui.

The computer can discriminate the differences in electrical current waveforms that cannot be identified by human eyes, which enables highly accurate virus classification. In addition to coronavirus, the system was tested with similar pathogens — respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza A, and influenza B.

The team believes that coronaviruses are especially well suited for this technique since their spiky outer proteins may even allow different strains to be classified separately. “This work will help with the development of a virus test kit that outperforms conventional viral inspection methods,” says last author Tomoji Kawai.

Compared with other rapid viral tests like polymerase chain reaction or antibody-based screens, the new method is much faster and does not require costly reagents, which may lead to improved diagnostic tests for emerging viral particles that cause infectious diseases such as COVID-19.