In many ways, Verdox, a chemical engineering company from MIT, has had a wonderful year. The carbon emissions (Meeting the challenge of carbon removal) and removals startup, which launched in 2019, announced $80 million in funding in February from a group of investors including Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. Then, in April – after being recognized as one of Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s Top Energy Pioneers of the Year – the company and partner Carbfix won the $1 million XPRIZE Carbon Removal award. It is the first round of the Musk Foundation’s four-year, $100 million competition, the largest prize awarded in history.

“While our core technology has been supported by significant improvements in performance metrics, this external feature makes our vision even more meaningful,” said Sahag Voskian SM ’15, PhD ’19, Co-Founder and Chief Technology Officer at Verdox says. “It shows that the path we have chosen is the right one.”

Demand for carbon sequestration technology may have intensified in recent years, as scientific models have strongly demonstrated that any hope of avoiding catastrophic climate change means limiting CO2 concentrations (Meeting the challenge of carbon removal) below 450 parts per million by 2100. Alternative energy will only get humans so far, and large-scale CO2 removal will be an important tool in the race to remove the gas from the atmosphere.

Voskian began developing the company’s cost-effective technology for carbon capture in T’s lab. Alan Hatton, Ralph Landau Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT. “It’s exciting to see an idea go (Meeting the challenge of carbon removal) from the lab to a viable commercial product,” says Hatton, the company’s co-founder and scientific advisor, adding that Verdox quickly overcame the first technical problems faced by many start-up companies. “This support adds credibility to what we do and really supports our process.”

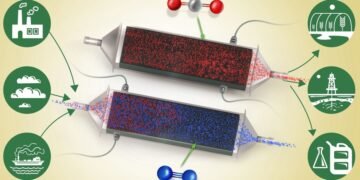

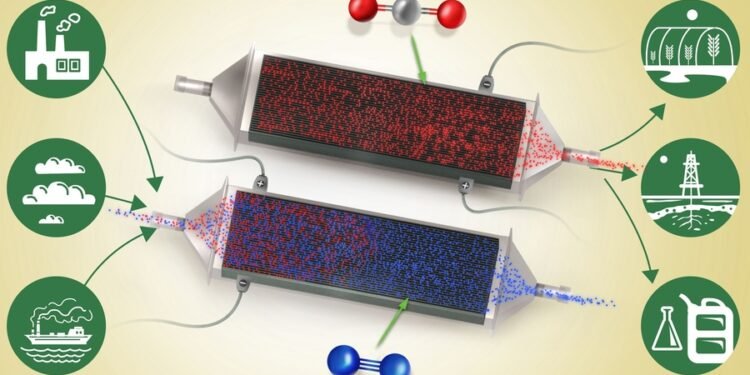

At the heart of this system is technology that Voskian describes as “good and efficient.” Most efforts to capture carbon from streams or the atmosphere itself require a lot of energy. Voskian and Hatton proposed a strategy of electrochemistry that makes carbon capture seem like a no-brainer. What they have created is a type of battery: conductive electrodes covered in a compound called polyanthraquinone, which has an attractive property for carbon dioxide under certain conditions, and has no affinity for CO2 when released those conditions.

When the low voltage works, the battery is charged, reacting to pass the CO2 molecules and attract them to its surface. Once the battery is full, CO2 can be released from the voltage converter as a stream of clean gas. Hatton says,

“We have shown that our technology works at a wide range of CO2 levels, from the 20% or more found in cement and steel water, to the 0.04% spread in the air itself,” Hatton says. The science of climate change suggests that removing CO2 directly from the atmosphere “is an important part of any mitigation plan,” he added.

“It’s an academic breakthrough,” says Brian Baynes PhD ’04, CEO and co-founder of Verdox. Baynes, a chemical engineering lecturer and former Hatton Fellow, has several starts to his name and a history as a venture capitalist and mentor to young entrepreneurs. When he first encountered Hatton and Voskian’s research in 2018, he was “interested in their technology that showed it could reduce energy consumption for some types of carbon capture by 70% compared to other technologies,” he said. – said. “I was encouraged and impressed by this low footprint, and told them to start a business.”

Hatton and Voskian had never run a business before, so they asked Baynes to help them get started. “I usually turn down these requests because the price is usually higher than the surface,” Baynes says. “But this new thing can have a breakthrough in climate change, I see it as a rare opportunity.”

The Verdox team is under no illusions about the challenges ahead. “The scale of the problem is huge,” Voskian says. “Our technology will be able to capture megatons and gigatons of CO2 from sources in the atmosphere.” In fact, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that the world needs to remove 10 gigatons of CO2 per year from 2050 to maintain global warming.

To grow effectively and at a pace that can meet the global climate challenge, Verdox must be “a company that works with technology”, as Baynes puts it. This means, for example, ensuring that its carbon emissions system offers a clear and competitive price advantage when delivered. No problem, says Voskian: “Our technology, because it uses electricity, can be easily integrated into the grid, working with solar energy and wind and plug-in The Verdox team believes its carbon footprint will exceed that of its competitors by orders of magnitude.

The company overcame a number of technical problems while growing: to allow the carbon capture battery to work for hundreds of thousands of cycles before its efficiency decreases and to improve the chemical polyanthraquinone in the device to be even an option for CO2.

After reaching the critical point, Verdox is now working with its first announced commercial customer: aluminum company Norwegian Hydro, which wants to eliminate CO2 by eliminating its emissions while switching to zero-emissions production. carbon.